For many people failure is due to nothing more than lack of confidence. When confidence levels continue to decline it leads to the pernicious cycle of the fear of failure. In most corporate cultures this is overcome by peer pressure, or a proven support network that people trust. It is not a conscious process, but simply the natural development of human behavior. However, what happens in the absence of third party incentives, or peer support, when the loss of confidence resulting from the cycle spirals into performance malaise and declining self-esteem? The effects can be sudden and devastating.

It’s a beautiful day to solo. My flight instructor stands on the runway, and waves. He is confident that I’m ready. I’ve often wondered what is in the mind of the instructor as he, or she, releases the tether. Curiously, I have never asked.

It’s easy. I’ve done this many times before. I know the airport pattern well. Pushing the throttle to full power (approximately 2500 rpm) the plane moves slowly across the approach threshold. I’m rolling down the runway for the first time, alone. The propeller’s clockwise torque causes the plane to drift left. Slight right rudder holds the airplane perfectly on the centerline. I feel the lift, nose up know, and trim the plane for the best rate of climb (70-75 knots). AT 400 feet AGL (above ground level) I turn left 90 degrees to the crosswind and continue to climb. Approaching the downwind, I’m more relaxed and prepare for the longest leg of the ride.

Turning downwind at 1000 feet AGL, I reduce the power to 2000 rpm and 90 knots of air speed. I’ve been in the air about three minutes now, and the downwind leg takes about the same time. I settle in and enjoy the ride. When I look left the airport is beginning to appear off my wing as I fly parallel to the runway. I look to my right. No one is there.

By the time I complete the downwind leg the tower controller has cleared my approach for landing. I begin the descent by making the first of several wing flap settings in preparation for the base leg turn. Turning 90 degrees to the base leg, I continue to reduce power while adding flaps. I’m at 70 knots descending at 500 feet/minute. The runway appears just forward off my left wing, and I prepare to turn on the final approach course.

The plane is now at 500 feet AGL and I am on short final, nose on the center line and approximately one half mile from the approach end of the runway. My left hand rests lightly on the flight controls. Right hand gently on the throttle. I’m completely relaxed, and touchdown is just moments away. I’m reminded that I am not an inanimate appendage of the airplane. The plane is the natural extension of me, and entirely under my command and control. I Check the airspeed. Exactly 60 knots, 200 feet AGL and approaching the runway.

With full flap extension, I cross the runway threshold and reduce engine power to idle. Gently applying back pressure on the flight controls, the indicated airspeed slows gradually . . . 55 knots . . . 50 . . . 45 . . . then 40, and as the nose of the airplane raises slightly, I feel the wheels softly touching down. Main gear first, then the front wheel on the centerline of the runway. The ground speed is now approximately 35 knots. I retract the flaps and, and with the maximum back pressure on the controls, brake firmly on the rudder pedals to a full stop.

My instructor gets into the airplane and we taxi to the fuel station. Very little is said. We both know the felling, now. A mutually shared fellowship. A common respect. I am a pilot, now. A distinction I will share with very few others for the rest of my life.

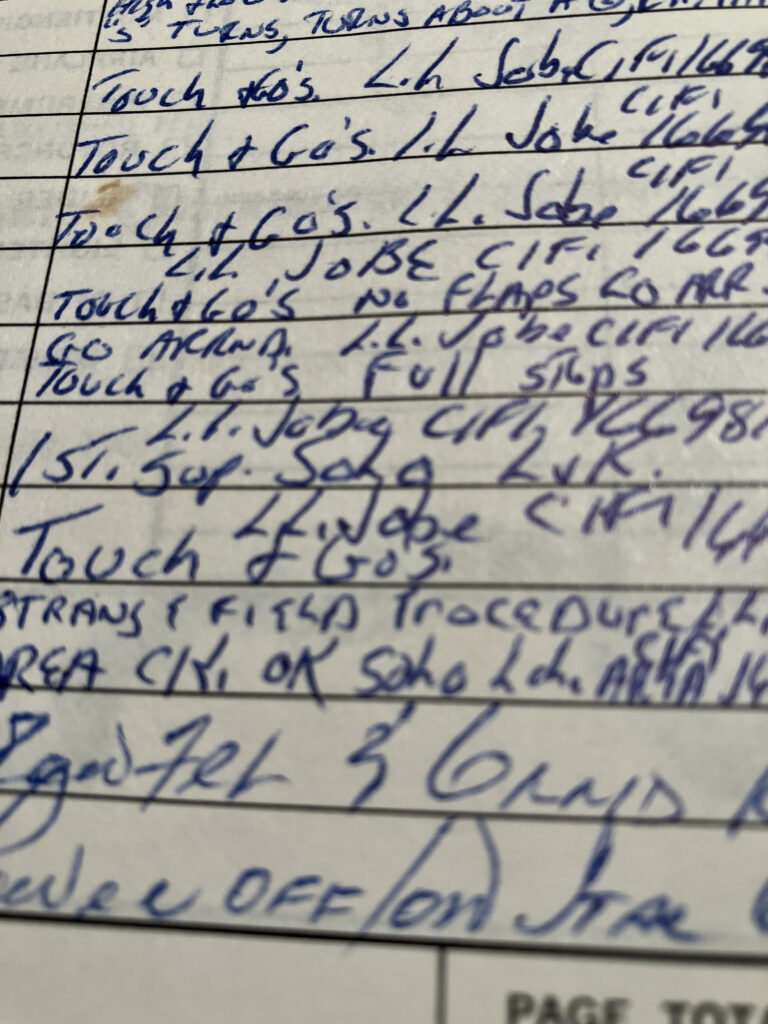

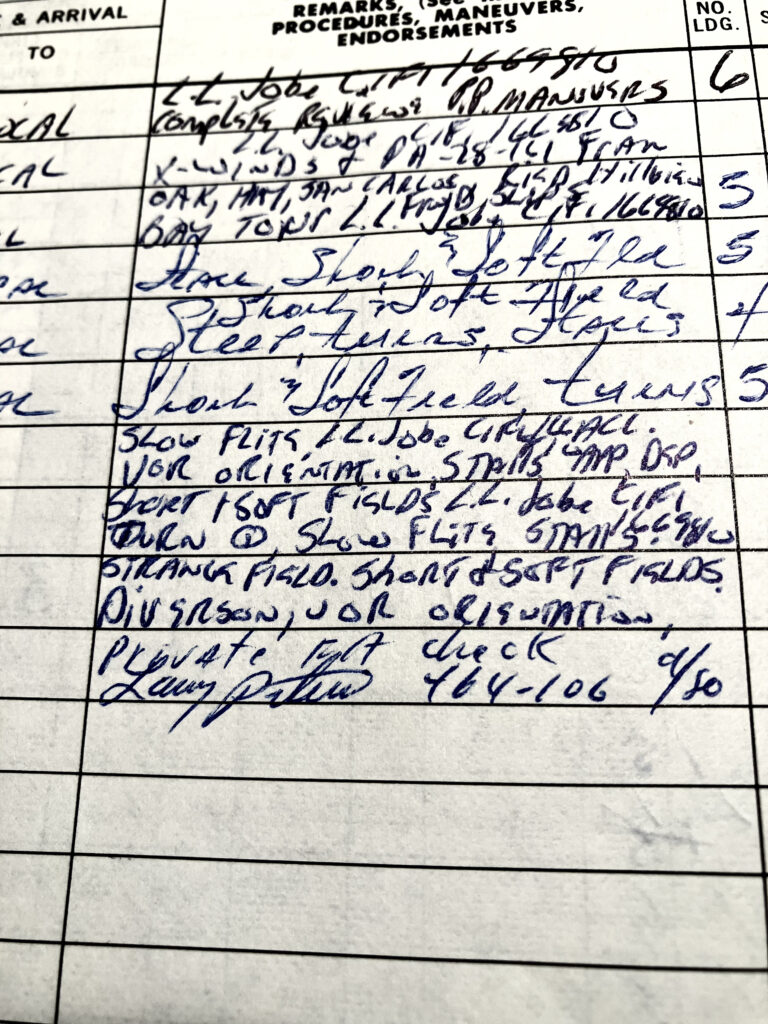

After parking the airplane we chat briefly and my instructor endorses my log book.

Soon he is gone, and I’m left alone. No applause. No celebration. As I walked across the parking ramp brimming with confidence my gait began to acquire the celebrated “solo swagger”. I was officially a pilot now, and for the rest of my life. I was ready to fly!! And, this is when the lesson was learned. Because, It would be weeks before I found the confidence to get back in the airplane again.

My flight instructor had left me with practice instructions for the next few hours in the airplane. I was told to stay within 25 nautical miles of the airport and practice the basic flight manoeauvres that I had learned. It’s well documented that 80% of student pilots drop out of primary training. Most students will stop just before, or just after, solo. Commonly referred to as the “solo plateau”. There is no clear evidence why, but the reason appears to be self-evident. In the days ahead it was my intent to continue my training as planned. But I failed to follow through even though there was no practical reason. I lived less than 5 miles from the airport and had the money, time, confidence and motivation to continue. Or, did I?

More than once I was on my way to the airport, but found a reason to return home. On several occasions I was in the midst of the pre-flight inspection when I stopped and left the airport. It soon became clear to me that in the absence of my instructor, who provided both peer pressure and my support network, I was beginning to lose confidence. I had to admit that I was beginning to exhibit some fear of getting into the airplane alone. I was never afraid to fail, but failing because of fear was inconceivable to me. I soon returned to the airplane, although my full confidence did not return as quickly.

It wasn’t long before I scheduled practice sessions with other students. We were not legally in the plane together, but we did it anyway and shared the expense. We built a network of collective confidence in ourselves, and each other. Not everyone finished. For some it was more work than anticipated. Others established new priorities. There was always the issue of money, and some just lost interest. But no one failed because of fear.

My instructor was a great guy, and became a good friend. Some years later he retired as a Captain for UA. As he endorsed by log book for the private pilot check ride, his last words were, “No matter what happens, don’t quit.”

Larry Peters was notorious for his intimidating style. I thought I could get by on my stick and rudder skills alone. I was wrong. Several times during the ride Peters said I needed more training, and asked me if wanted to return to the airport. But, he never ordered me back. So, I just kept flying. It was terrible. Finally he said, “I’ve seen enough, take me back.”

There had been no conversation during the half hour return flight. I refuelled the plane, then parked in front of the FBO where we had started. Peters debriefed the flight while we were in the plane. He was justifiably critical of my lack of preparation, and obvious arrogance. He asked if I had intended to waste his time. I acknowledged that he was right, and apologised. Then he said, “You know what you have to do, then.” I said, “Yes.” He finished by saying, “Ok, nice flight. I can sign you off.”

Obviously, Larry Peters had his own way of doing things. Today, FAA Flight Examiners are required to follow a tight script. I’m certain the outcome would be much different.

Châz